Ironically, not treating the common good as primary helps better instigate pursuit of that common good. This third and final post on being grounded in heaven seeks to explore how it is the heavenly-minded who actually find their way beyond the fragmentation of life and provide the greater societal good as well. The Kuyperian tradition has heralded the common good and the wholism of discipleship over against a merely ethereal vision of the gospel or a reductively religious or pious version of discipleship, respectively. I want to call for three cheers to each of those correctives and yet also to suggest that Kuyperianism hasn’t itself tended to prioritize the central imaginative and habitual emphases that actually form Christian women and men to live out that vision. To best reach those Kuyperian goals, we need to return to more catholic or central Christian convictions and practices. Two elements will be central to ensuring that the common good is pursued and that personal wholeness is increasingly enjoyed: the first involves attention to the contemplative life and not merely the active life, while the second concerns a renewed appreciation for the place of self-denial or what has been called Christian asceticism. In so doing we will be better resourced with the power for the good life and better aware of the price paid by love in pursuit of that common good.

The Contemplative Life for the Sake of the Active Life

When we talk about the common good, we tend to focus on activity: community development, works of mercy, investment strategy, reweaving the fabric of our civic culture, and the like. All are good things, and Jesus not merely proclaims forgiveness but also restores persons to relational and social wholeness by healing and casting out demons. We have Christian reasons for these concerns. But Jesus also displays the importance of tending to ourselves that we might serve faithfully and sustainably over the long haul.

One of the most important additions to the training of mental health counselors in recent years has been a renewed focus on self-care. While it can easily sound petty (the need for “me-time,” as a friend put it), the curricular focus has arisen out of an awareness of the burden that those involved in clinical care bear and the way it functions like a ticking time bomb if not handled intentionally. Similarly, professional trainers now engage in a constant calibration of what is called “load management” to make sure that professional athletes not only perform at the peak of their excellence but also that they rest and diversify their workload so as not to create medium- and long-term hindrances. We are no longer simply trying to get athletes to their 10,000 hours of focused practice so that they might become excellent, but we are also told to vary their training regimens and to watchfully guard them from overexertion.

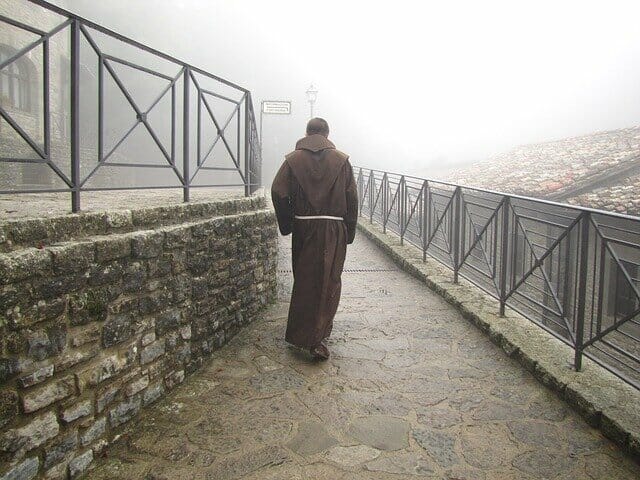

Similarly, Christians have always emphasized the need to develop both the contemplative and the active life. As we are called to love our neighbor actively and seek the good of the city, so we are also called first to the contemplative life of devotion: to prayer, to scriptural engagement, to meditation, to sabbath rest. We need to acknowledge that the faith and work movement and the Kuyperian theology that has so influenced it have had much to say about the active life but rather little about the contemplative life. And we need to admit – as therapists and trainers and many others acknowledge in their fields – that the active life of Christian discipleship isn’t ordinarily going to outrun the sustaining power of the contemplative life of Christian communion with the triune God.

What would it look like for Kuyperians to say that the common good and personal wholeness both need not only Martha-like service but also Mary-like adoration? Luke 10:38-42 has been pivotal in leading Christian men and women through the centuries to prioritize spiritual means of grace that feed their souls, out of which they have the strength and solidity to give themselves up for others. Calvin’s vision in this regard, as described well in books by Matthew Myer-Boulton and Julie Canlis, was not to kill monastic piety but to universalize it amongst the church, that every Christian would live out the rhythms of devotion to God and thereby be transformed to love and serve sacrificially. Routines of prayer, the ministry of the Word, the sacramental life, fellowship and hospitality, fasting and especially sabbath rest are like the electrical pathways through which the energizing love of God flows and apart from which the impact of the common good and personal wholeness will not happen. A renewed attention to the energizing and sending force of the contemplative life funds or provides the power for the needed active life of mission and service.

The Worry About Christian Asceticism

There’s a second way we need to further hone our thinking about the common good, by retrieving and refining the Christian commitment to self-denial and what has been called asceticism. Asceticism traditionally refers to any subordination of a lesser good for the sake of a future greater good, what financiers would simply call investment but what many Christians have found imprudent and even dangerous. We need to consider why it’s fallen under suspicion and rethink if afresh, if we are to honestly own up to the necessary price of personal wholeness and of truly pursuing the common good which never comes cheaply. Herman Bavinck and other Kuyperians have chided ascetical self-denial for a number of reasons. It can lead to legalism, to be sure, and it can also lead to a sense of works righteousness or spiritual pride. At times it leads to extra-biblical pieties being treated as if they were essential elements of Christian discipleship and, thereby, lead many Christians to unnecessary anxiety or shame. All of these are valid concerns. In some medieval, monastic settings and in some pieties today on the left and the right, asceticism can take on legalistic and excessive exuberance.

Animating more recent critiques of asceticism or self-denial have been claims that it involves a Greek or Platonic denigration of the material realm and is therefore the latest version of Gnosticism. The claim is made that asceticism involves demeaning bodies and sex or this earth and our concern for its flourishing. Ascetics bash the earthly and elevate the heavenly. So the story goes. A call to heavenly-mindedness, to contemplative practice, or to ascetical self-denial then only doubles down on dualism by not merely saying that the earthly isn’t divine but also by saying it’s lesser or evil than the spiritual sphere.

Yet self-denial is woven into the call to love. Love always bears a cost or involves sacrifice. Love bears all, the apostle says (1 Corinthians 13:7). Love won’t come cheap, and so we need to ask what Christ bids us to deny or to sacrifice in our love for him and for our neighbor, especially for the least of these. Not for nothing is the single most read portion of John Calvin’s writings his discussion of asceticism and self-denial. While there were and no doubt are mangled versions of asceticism, the call to self-denial is ingrained in the summons to follow Christ as a disciple and to be baptized into his name.

Rethinking the Call to Self-Denial

We are to love the self and pattern our love of others along our love of self (so Jesus’s rendition of the second great commandment), and yet love of the self is viewed as a detrimental and evil practice. The later Christian tradition has spoken of self-love in this complex, multi-form fashion as well, gesturing toward this complexity. Can we say more about the nature of such an asceticism? Gleaning from John Calvin, I think four facets might be summarized as significant for shaping a distinctly evangelical approach to self-denial.

First, Christian asceticism is not merely or even primarily about “contempt for the world” as such. Any notion of contemptus mundi which is to prove serviceable to the gospel must be coordinated with a contempt for the self. The world as such, and its moral nature, flows from the way in which it is engaged by human creatures before God. Thus, riches or poverty may be received rightly or wrongly, depending upon the posture with which one possesses that much or that little. Stuff isn’t problematic so much as my own disordered love of stuff – this is not about growing to despise “things out there” but about recalibrating my love in here for those things.

Second, Christian asceticism is not merely or even primarily about contempt at all. First and foremost, contempt of the world and of the self must be preceded by delight in the good things of life: God and all things in as much as they participate in God’s bliss and blessing. In commenting upon 2 Cor. 2:14, Calvin insists: “the only way to make right progress in the Gospel is to be attracted by the sweet fragrance of Christ so that we desire Him enough to bid the enticements of the world farewell.” Hence, present restraint (as described in Inst. III.x) must be fueled by meditation upon future blessing (as described in the immediately preceding section: III.ix). And present restraint may not take the form of hatred of the world as a good; indeed, Christians must be able to delight in the goods of the world (even if it may involve seasons of abstinence for the sake of stoking a greater love).

Third, any call to denial or renunciation is a temporal reality and makes sense only in a particular historic frame of reference: the pilgrim avoids enjoying the route, however scenic it may be, to any extent that would lead them away from yearning for their final destination; similarly, the Christian contents her- or himself with God’s provisions for the day and avoids fostering a yearning for greater earthly good, lest they forget the heavenly satisfactions that await them in glory. Christians do live in a state of grace, so that there are temporal goods to be enjoyed. Christians are not yet in the state of glory, so they must expect to experience delayed gratification. “Since the eternal inheritance of man is in heaven, it is truly right that we should tend thither; yet must we fix our foot on earth long enough to enable us to consider the abode which God requires man to use for a time. For we are now conversant with that history which teaches us that Adam was, by divine appointment, an inhabitant of the earth, in order that he might, in passing through his earthly life, meditate on heavenly glory.”

Fourth, Christian asceticism will be guided by the church’s authoritative teaching of Holy Scripture (only) in so far as the Scriptures do speak and then by the discernment of individual consciences shaped by that scriptural revelation. Thus emphasis will be placed upon practices such as keeping the sabbath day holy, the giving of tithes and offerings, and occasional fasting, which find explicit warrant in God’s Word. Still further, prayer remains the most profound ascetic practice and is not only commanded but exemplified and illustrated throughout the Scriptures. In prayer, Christians turn from their restless activity to rest their anxieties and needs, their aspirations and joys, their very selves, upon God. While individuals and families may opt to include other rites or rhythms in their spiritual practice from time to time and with regard to varying challenges or callings, church communities will focus upon these scripturally warranted practices in their discipleship.

In conclusion, the kingdom of God warrants investment – it asks nothing but we are asked to give up all that we have. To embrace Christ is to let go of ourselves, which is the way of life, wholeness, and the real contribution to the common good. If we want to enjoy more of that peace here on earth, then we need to be grounded in heaven.

Michael Allen teaches at Reformed Theological Seminary in Orlando, where he serves as the John Dyer Trimble Professor of Systematic Theology. He has previously held the Kennedy Chair at Knox Theological Seminary, lectures widely, and has held a visiting fellowship at Cambridge University. He has written many books and essays. These three posts are related to and in places excerpt material from his latest book, Grounded in Heaven: Recentering Christian Hope and Life on God.