If there’s one thing markets demonstrate, it’s how important future expectations are for living in the present. Sell. Short. Buy long. These decisions are shaped by confidence (or lack thereof) in the future of a given investment. Perhaps most painful are those occasions when certainty plummets, and the market simply dries up. Recessions and slowdowns appear stagnant, and they manifest a lack of confident hope. What’s true of markets also affects the moral and spiritual life. Theologians and philosophers speak of the way in which hope shapes one’s life or, put more technically, eschatology (the study of last things) impacts ethics. We wonder about what can be reasonably expected in the future, from asking “will home prices keep going up?” to also inquiring “will my work have any significance?” The sorts of answers we find shape the way we live.

Our Treasure In A Field

“Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! According to his great mercy, he has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead” (1 Peter 1:3). Christians have “living hope,” a sure and certain expectation that the hope born within us will bring blessing, all because Jesus Christ has been raised from the dead. His triumph over the grave and his place on high even now give us confidence and certainty. The New Testament authors don’t hesitate to use the language of investment to speak of our response: “The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which a man found and covered up. Then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field. Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearls, who, on finding one pearl of great value, went and sold all that he had and bought it” (Matthew 13:44-46). Whether that investment involves real estate or commodities, the blessing of God can be trusted because the earnest payment has been made: Jesus Christ is risen from the dead. Christians have a resolute hope, and as such they live accordingly.

But the certainty of Christian hope hasn’t always translated to clarity and consensus regarding the precise shape of that hope. True, Christians have felt duty bound to leave superficial optimism and despairing pessimism behind for the greater calling of hope, but they have differed at times over precisely what we hope for. Another way of putting it would be to say that Christians have believed that Christianity is a trustworthy way, even if its eschatological or final course has been much debated. In this and two later blog posts, I want to explore ways in which our living hope shapes the way we live today and to consider areas in which modern Christians should reassess that hope and those living implications.

Dispensationalism and the Kuyperian Movement

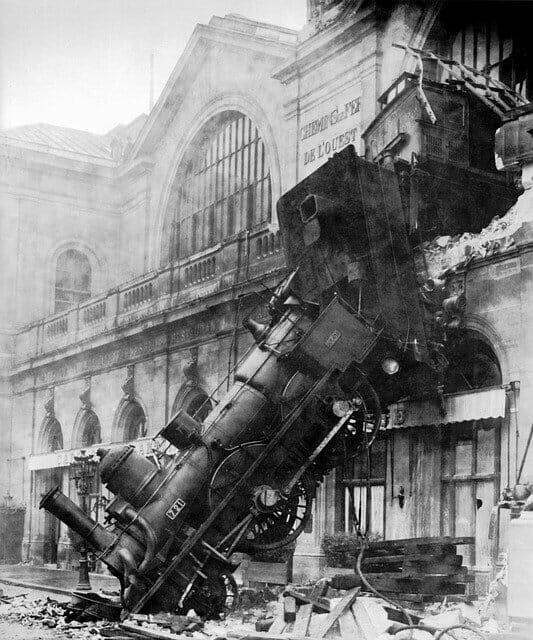

The late nineteenth century was a time of major civilizational optimism. Industrialism could celebrate triumphs, opening up new frontiers with railroads and fine-tuning the mass production process. Revolutions in Europe and a civil war in the US were in the rearview at this point. When mainline Christians decided to launch a new periodical to address matters of religion and culture, they titled it The Christian Century, showing their cards as real optimists who believed that the years ahead would involve progress and growth. This would be the century of the kingdom of God.

Dispensationals did not have the same optimism about the Industrial Revolution that many others had.

Others did not share that optimism about culture. In Great Britain and in the United States, a new movement emerged in these decades that read the Bible in a new and harrowing fashion. John Nelson Darby’s followers became known as dispensationalists, because they believed the Bible spoke of different dispensations or epochs. Among their many principles was an expectation that the end times would involve the utter destruction of this world. They also popularized the expectation that the far side of judgment day would be an ethereal existence in the heavenlies or the clouds. Not surprisingly preachers and evangelists (such as Dwight Moody) would speak of how it was unwise to shine the brass on a sinking ship. While it would be too much to say that they abandoned concern for the common good (for they did still offer any number of social services in places like center city Chicago), they did undercut any theoretical explanation for why caring for the common good fits with or anticipates our eternal destiny. One of the hallmarks of fundamentalism in the early twentieth century was an otherworldliness that manifested itself in keeping culture and society at arm’s length.

Dispensationalism was an international influence. Though begun in Great Britain and grown in the US, Dutch thinkers like Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck viewed it as a live threat to Christian society in continental Europe. Their Neo-Calvinist or Kuyperian influence sought to respond to the tendencies of dispensationalism. Whereas dispensationalists emphasized the judgment of the earth by fire at the end, the Kuyperians would point to language that speaks of the restoration and liberation of the world by God’s grace. If dispensationalists looked to an otherworldly, soulish existence, the Kuyperians emphasized the resurrection of the body and the location of the new creation. In the face of dispensationalism’s tendency toward disembodiment and disavowing worldly affairs, Kuyperian Neo-Calvinism has celebrated creatureliness and embodiment, finitude and earthiness.

The Benefits of a Kuyperian Approach

I would suggest that dispensationalism functions like a spiritual malnutrition, failing to provide necessary intake for optimal health. In that reading of Scripture, the enjoyment of God’s spiritual presence upon our death – a soulish or spiritual reality before the resurrection of our bodies – leads to a loss of being nourished by the hope of eventual resurrection and later dwelling in a new heavens and new earth. To follow the metaphor, the Kuyperian approach has served like an infusion in the critical care section of a hospital, reinjecting necessary nutrients and helping to bring a patient out of a dire situation.

There’s always a danger in receiving medical treatment, however, that critical care measures will not morph into long term rhythms of health and wellness. The therapies of the ICU are not the same as the mature rhythms of human wellness, diet, and exercise. While an IV may be necessary for a season to provide nutrition, fluids, and medicine to combat a virus or to help one recover from the trauma of surgery, eventually the body needs to gain those things apart from such an invasive measure. This kind of challenge can face us theologically as well. There’s always the danger that our enthusiasm for a crisis intervention can hinder us from finding longer term balance.

When I was recovering from a surgery involving my digestive track, I was provided soft foods that wouldn’t give my intestines a run for their money. In that season, the intake of foods that wouldn’t provide any resistance outweighed any desire for a balanced diet with all the varied nutrients. Thankfully, that diet contributed to a healthy recovery. Even more thankfully, that diet was able to change in the days and weeks to follow so that I could expand my intake and begin to eat at least a somewhat wider array of foods. Might we also benefit from asking about what a more mature Kuyperianism could involve?

The Dangers of a Kuyperian Approach

How might the Kuyperian infusion of earthy hope hinder us in the long run? It has helped us recover or retain a commitment to certain Christian commitments like the resurrection of the body, but it may sometimes crowd out or distract from the central Christian hope, namely, that we look forward most of all to the eternal presence of God. I think we could call this danger “eschatological naturalism,” that is, the idea that while God graciously gets and gives us eternal blessing, he is not necessary to or defining of that blessing itself. You might say God becomes an instrument who provides our hope, though he himself is not that hope. That hope instead is identified with the renewed environment or the resurrected body, with the advent of world peace and the absence of human sin, with psychological wholeness or relational reconciliation. All good things, but they can be imagined and desired without God.

In fact, I’m not merely speaking hypothetically as if this could happen. In certain strands of the Kuyperian-influenced world, it has happened. Now I don’t think that people have intentionally aimed at excising God from their vision of glory, but that’s just the point. This kind of problem can arise unintentionally precisely because the Kuyperian emphases (which are good correctives) fit so snugly with what we are trained by the wider culture to value. Our world says that your body matters – against the dispensationalists, Kuyperians remind us that God values the body so much as to raise it anew. That the Kuyperian approach overlaps with non-Christian values is no sign of its falsehood, but it ought to be a reminder that we must be vigilant here to not allow it to provide cover for unrestrained or undisciplined desire.

Some Kuyperians paint a picture of the new heavens and new earth, barely bothering to mention God as the central occupant. Some have gone still further and actually chided those who sing of his heavenly presence as if they were “singing lies in church.” Neither view is necessary for a Kuyperian – in fact, Kuyper himself fell into neither of those errors. But we might be naïve if we didn’t observe how snugly Kuyperianism can provide a religious justification for lots of things we are raised to prize otherwise: political progress, environmental justice, psychological health, bodily vigor, and so forth. And we would be in danger if we weren’t wise enough to see that Kuyperianism has not heralded the elements of our hope that run more directly against those of the secular culture, namely, that God is the central or defining element of our future.

In Conclusion

What might a mature hope look like, one that has been strengthened by Kuyperian emphases but that doesn’t reduce itself to those interventionist elements? What would wholeness look like in terms of our eschatology and its corresponding lifestyle or ethic? In the following two posts, I’ll seek to explain a more holistic vision that centers itself upon the heavenly presence of God to be enjoyed in the hereafter, while also remembering the ways in which that presence is enjoyed by embodied, resurrected humans in a new heavens and new earth. Clarity about the shape of our certain hope will also prompt different investments of time because it will involve a reordering of longing and desire. We’ll look to ways in which we should think and express a living hope today, rhythms in which our eschatology shapes our ethics for good or ill. In so doing I wager that we will see why C. S. Lewis said: “Aim at Heaven and you will get earth ‘thrown in’: aim at earth and you will get neither.”

Michael Allen teaches at Reformed Theological Seminary in Orlando, where he serves as the John Dyer Trimble Professor of Systematic Theology. He has previously held the Kennedy Chair at Knox Theological Seminary, lectures widely, and has held a visiting fellowship at Cambridge University. These three posts are related to his latest book, Grounded in Heaven: Recentering Christian Hope and Life on God.